Venezuela’s Cryptocurrency Represents a Big Problem

Why does anyone use cryptocurrency?

The biggest real use case today remains evasion of third party control in holding and transacting assets. This control can come from governments, banks, or other intermediaries.

People use cryptocurrencies to make purchases online that they would prefer others didn’t know about. In countries like China and Argentina, bitcoin has been used to evade government controls over capital flows. In Cyprus, bitcoin has been used to avoid government seizures of assets and bank accounts. In Venezuela, bitcoin has been used as a store of value in the face of nearly 10,000% annual inflation. People have also used cryptocurrencies to fundraise in ways that would otherwise be subject to regulation… securities laws, money transfer regs, know your customer rules.

But it’s not just individuals that use cryptocurrencies in these ways.

Many large companies famously hold bitcoin on their books in order to pay off hackers in case of a cyberattack. Anecdotally, I have heard of Fortune 500 executives attempting to use bitcoin to transfer funds between regional subsidiaries of their companies, avoiding capital controls in certain jurisdictions.

If individuals and corporations use cryptocurrencies to evade third party controls, why wouldn’t governments do the same? Governments, after all, do not exist in their own sovereign bubbles. They exist on a global gameboard in which other players are constantly writing new rules. These rules can be explicit — in the form of sanctions or trade barriers — or implicit — in the form of propaganda campaigns.

Governments attempting to use cryptocurrencies to evade the rules imposed by another regime… it sounds like the plot of a cyberpunk novel. Actually, it’s just 2018.

Defaulting On Your Citizens

Three and a half years ago in Caracas, the Venezuelan president issued a statement threatening legal action against a Harvard professor. The professor, a former cabinet member of the Venezuelan government, had left his homeland twenty years prior. Now the president was accusing him of waging economic warfare on his home country. “We have the proof,” said the president, “in your declarations and articles, up there in your mansions where you live with money stolen from Venezuela.”

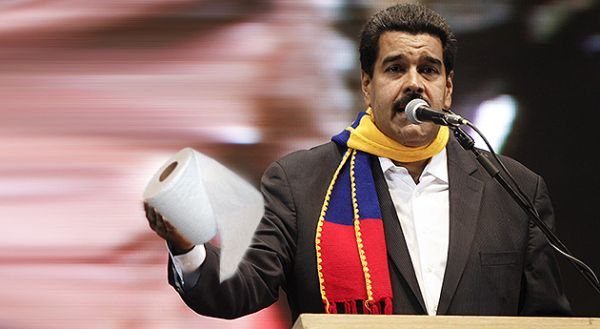

The Venezuelan president, a man named Nicolas Maduro, came into politics through the unions and rose to be Hugo Chavez’s righthand man. Following Chavez’s death in 2013, Maduro was narrowly elected to succeed his old friend. He carried on Chavez’s economic policies, which had long since caught up with the Venezuelan economy.

Between 2012 and 2014, Venezuela’s currency, the bolivar, lost 90% of its value. Electricity blackouts became increasingly frequent throughout the country. Government price controls and restrictions on foreign currency transactions resulted in shortages of everything from cooking oil to toilet paper. The running joke was that this was all the bolivar was good for…

Yet the man at the head of it all was blaming a Harvard professor thousands of miles away in Cambridge. The professor in question, Ricardo Hausmann, had recently co-authored an article simply titled “Should Venezuela Default?”

The article addressed a bizarre dynamic: despite its failing economy, Venezuela was continuing to make good on its extreme debt burden, making double-digit interest payments to bondholders every month. Venezuela had often been praised in international capital markets for continuing to find ways to make these payments.

What Hausmann asked in his article, however, was whether this was really so laudable. The bond payments went to large, international asset managers — hedge funds and mutual funds. Meanwhile, Venezuela had long since defaulted on its people. Was the regime choosing hedge funds over hungry citizens?

Hausmann’s article was exactly the sort of damaging message that Maduro wanted to avoid.

Sanctions and Evasions

In 2015, US President Obama issued an executive order sanctioning certain Venezuelan individuals whom he deemed to be contributing to the humanitarian crisis there. In August of 2017, building on Obama’s edict, Donald Trump issued an order of his own. Trump’s order was more expansive: it prohibited certain dealings in Venezuelan securities, including government bonds.

Three months later, Maduro finally did what Hausmann had called for years prior — he slipped up on a payment and he defaulted on those newly-sanctioned government bonds.

Normally in the case of a sovereign default, the debtor nation can negotiate a deal with its bondholders. The country might offer to exchange the defaulted bonds for new bonds that give them more time to repay their creditors. This is called a restructuring. Because of the sanctions in place, however, US bondholders — Wall Street banks and asset managers — could not engage in a restructuring with Venezuela.

When a country is unable to restructure, it becomes effectively locked out of capital markets. Patria non grata as far as lenders are concerned. This makes it very difficult for the country to borrow and impossible to borrow at a favorable rate.

If only there was a way for Maduro’s regime to evade regulation in a fundraising process — a way to tap investors for money who could not presently engage in his investment offering.

Over last two years, a fundraising mechanism has developed that has seemed at times to exist outside of any regulatory framework. It is called an initial coin offering.

An initial coin offering is the creation of a new cryptocurrency that is sold to the general public, usually in exchange for some other, pre-existing currencies or tokens, such as bitcoin or ether. Over six billion dollars went towards initial coin offerings in 2017 alone.

If individuals and companies were managing to fundraise using this mechanism, why couldn’t a government?

This is what the Venezuelan regime seemed to spot last winter. If Maduro could not go to conventional capital markets anymore, he would turn to cryptocurrency markets. Just as his citizens had begun employing bitcoin to avoid his problematic policies, he could now use cryptocurrency to avoid the United States’ sanctions.

Maduro’s scheme might have worked if he had been using his new tokens to fundraise from individuals and entities who were off the grid (and if he had the technical expertise to pull it off). Remember, however, that most of Venezuela’s bondholders are institutional asset managers, some of the most heavily scrutinized entities in the world. If they participated (and ever wanted to report profits), they would have to disclose this transaction to shareholders and policymakers and they would once more find themselves in trouble with the US State Department.

In case there was any doubt on this front, Trump issued a follow up to his initial sanctions, clarifying that the order “prohibits all transactions related to, provision of financing for, and other dealings in, by a United States person or within the United States, any digital currency, digital coin, or digital token that was issued by, for, or on behalf of the Government of Venezuela.”

So the Venezuelan cryptocurrency scheme does not work quite as Maduro’s government may have hoped. Their target investors would never risk touching the token. Nonetheless, the very fact that Venezuela undertook an initial coin offering introduces a new model for defaulted nation states looking to access capital. Cryptocurrency has already threatened many modes of government regulation, from capital controls to taxation. Have sanctions now joined this list?

Government use of cryptocurrency is not necessarily a good or a bad thing, but I would be remiss to not bring up here the state of Venezuela’s population. Maduro’s economic policies have long played an undeniable role in thehumanitarian crisis occurring in Venezuela. There has been much debate about their effectiveness, but the Obama and Trump sanctions were explicitly intended to pressure Maduro to improve the state of the country.

Venezuela’s most recent debt issuances to Goldman Sachs were termed “hunger bonds”; the bonds bailed out the regime from having to feel real policy pressure to improve the state of the country. The Petro, Maduro’s cryptocurrency, is intended to do the same thing, allowing his regime to circumvent sanctions intended to pressure it into helping its hungry population.

These are not freedom-preserving crypto assets. These are hunger tokens.

The Problem With Platforms

What is this story about?

It’s not really about leftist dictators, or toilet paper shortages, or sovereign defaults, or Donald Trump, or Goldman bankers.

It’s partially about a tragedy that is unfolding in Venezuela and the machinations of the government there to sustain that status quo.

It’s also about the problem with platforms. If you create a tool or platform for innovation, you probably have a vision for how it gets used… but ultimately you don’t get to choose. Maybe you built a platform to make the world moreopen and connected, but instead transformed how people’s data gets used. And maybe that, in turn, has resulted in a new and powerful paradigm forgovernment and corporate propoganda. Maybe you built a platform to enable censorship resistant money, but instead created a fundraising mechanism for corrupt governments and fraudulent parties.

Open platforms and tools necessarily take this risk. Even in the realm of security, where paranoia and edge-case thinking are commonplace, builders might not be adequately considering the ways in which their products and platforms can and will be used.

Addendum: Argentina

Venezuela’s issuance of a cryptocurrency is important insofar as it represents a new form of fundraise by a state actor — and a new way of evading sanctions. Thus far, however, it has not worked. This is in part due to inadequate technical expertise on the part of Maduro in implementing the initiative. It is also because Venezuela’s target investors are beholden to the sanctions. Even if they wanted to buy into the Venezuelan government’s cryptocurrency, in order for the investment to be recognized, they would have to report the purchase — and answer some very uncomfortable questions in US federal court.

But I think there is a way, another context, in which a cryptocurrency could have successfully helped a recalcitrant debtor nation access capital markets.

In order to examine this, we must return again to a few years ago in Latin America. This time our destination is Argentina.

In 2001 Argentina defaulted on its sovereign debt and engaged in a restructuring with their bondholders. Most of their bondholders (97% of them) accepted a deal that traded their old defaulted bonds for new bonds that paid them back in smaller increments over a longer period. This would constitute a more manageable debt burden for the country and at least some relief for the bondholders.

So why would anyone not accept the deal? That small percentage of bondholding hedge funds who refused… what were they thinking?

Well, it turns out there was some language in the old bonds that guaranteed that Argentina could not make any payments on newly issued debt without also paying off those old defaulted bonds. The “holdouts” (as that small group of hedge funds came to be called) waited until Argentina had issued and begun to pay the new debt… and then they sued the Republic of Argentina. Oh and those hedge funds? They also went out and bought up even more of the old bonds in the meantime.

Argentina called bullshit on this move and refused to pay the holdout funds. What ensued was a decade-long legal battle that at various points went all the way to the US Supreme Court, involved the seizure of an Argentine naval vessel off the coast of Ghana, and resulted in some very unbecoming language thrown around by hedge fund managers and cabinet ministers alike.

Amidst all of this, there was one moment that would not have been particularly memorable if it were not so relevant to the conversation around state-issued cryptocurrency.

In March of 2015, Argentina attempted to make a payment to its bondholders without also paying the holdouts.

The US courts declared that the payment would not be allowed. If my memory serves, however, (and admittedly it may not because this was a pretty stressful period all around) the courts did not say that the bondholders were not allowed to receive the payment. Rather, the payment was prevented by a quirk of the settlement system. Citibank needed to process it. The US courts stated that if Citibank, the intermediary, attempted to do so, they would be aiding and abetting Argentina in violating New York law. The US courts got their way and Citi did not end up making the payment.

The presence of a third party intermediary, in this case, was what prevented the payment being made (and in part prevented Argentina from maintaining its standing in global markets).

What if they could have issued payment to these bondholders in such a way that didn’t demand an intermediary? What if the government had used cryptocurrency?

Thanks to Antonio Talledo and Alejandro Machado for their feedback and for generally being excellent sources of knowledge on all things crypto and Venezuela. Thanks also to John Loeber for excellent comments and encouragement, as always. Thanks finally to Marjorie Kasten who taught me that if you build an open platform, you don’t get to choose how it’s used. All errata are, of course, my own.